Sometimes you just get lucky

Telling the story of Becky Smith's jai alai career

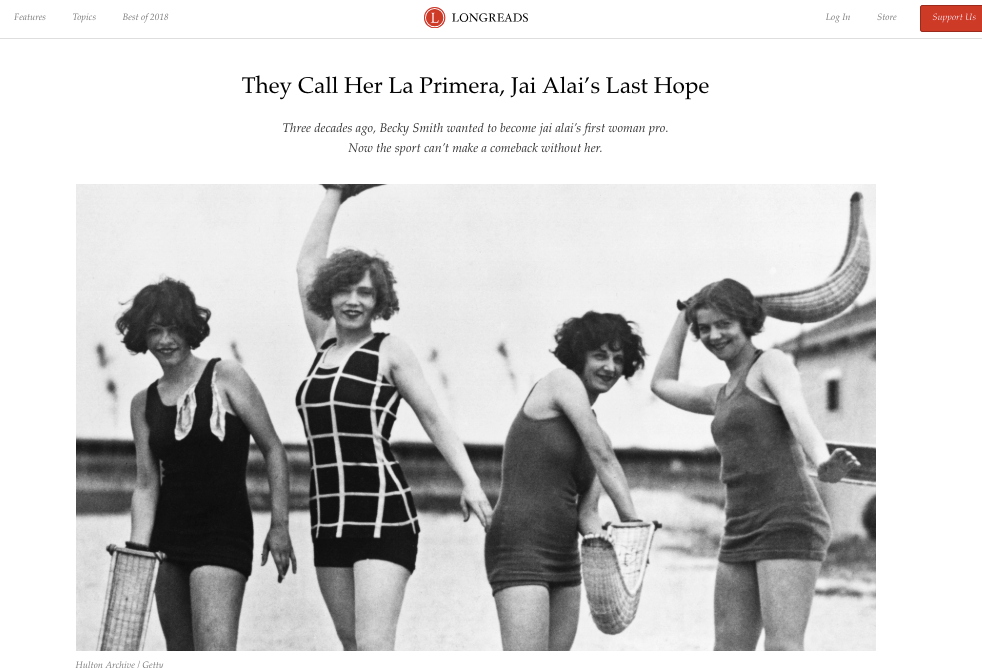

Earlier this month, I published “They Call Her La Primera, Jai Alai’s Last Hope” on Longreads. It tells the story of Becky Smith, who, in the mid-1980s, attempted to become the first female professional jai alai player (definitely in the U.S., probably in the world). This spring, over 30 years after she first tried, she signed a professional contract. At 54 years old, she accomplished her lifelong dream, and all these years later, she is still the first. The name she will wear on the back of her jersey will be a nod to this accomplishment: La Primera.

I received a reader request to talk about how this story came about. A good place to start is to listen to the episode of the Longreads podcast that dropped alongside the written story. In it, I talk with my editor, Matt Giles, about the making of the story. You can hear audio of my interview with Becky, including the exact moment we realized that we were talking about two different stories.

You see, I had no idea that Becky was playing jai alai again. I was calling her to talk about what happened after Sports Illustrated profiled her in 1987 — the last mention of her career I could find. She (understandably) thought I’d heard that Calder Casino in Miami was putting together a team and that she had recently tried out and made the cut. In her mind, why else would a journalist be calling her right now to talk about jai alai?

Sometimes, you just get lucky. This was one of those times. It was serendipitous and it was in that moment, just minutes into our first interview (we did two hour-long phone interviews, plus countless texts and emails back and forth), that I knew this was going to be a special story.

If you haven’t already listened to it, go check out the podcast (it’s about 27 minutes long) and then come back. I’ll wait.

Pretty cool, right? I continue to be awed by what audio folks are able to do; the first time I listened to the podcast, I cried, but maybe that’s because I was getting my period. Or maybe it was because it’s a genuinely moving story that I feel privileged to have gotten to tell.

A photo by Bill Frakes from SI’s 1987 photoshoot with Becky that did not end up being used in the story.

But let’s back up a bit.

Here is where it would be important to know a little bit about my Longreads column itself. I’m the sports columnist at the publication, which essentially means I’m writing a story each month. “Column” is probably not the right word for what I’m doing there, since these pieces have so far run between 4,000 and 5,000 words and have required weeks, if not months, of reporting and research. They’re pieces of longform narrative journalism.

This is also where I tell you again about my editor, Matt Giles. To take sole credit for the work of this column would be misleading, because the truth is that, in many ways, it’s a collaboration between Matt and myself. Matt is an alum of ESPN The Magazine, so he’s a sports nerd. This helps! Another cool thing about Matt is that when we first connected to talk about what this column might look like, I told him I wanted it to focus on female athletes whenever possible. I was open to covering men, but wanted to do as many women as we could. And even if we only covered women, I wanted to be the “sports columnist,” not the “women’s sports columnist.”

We have published three stories so far, with four more in the works or planned. They all focus on women. When I told Matt that was the direction I wanted to go, he didn’t bat an eye. We brainstorm ideas together, and we both bring stuff to the table. Sometimes they’re solely my ideas, sometimes they’re totally his, sometimes we chat things through and they’re entirely collaborative.

So back to Becky Smith.

I wish I could tell you that I came across her story and began to look into it, but that would be a lie. Matt had gone down a jai alai rabbit hole (as you do) and come across the names of Becky and her two sisters. He found the SI story and perhaps one other, and emailed me:

I was watching a 30 for 30 short about jai alai, and I fell down a rabbit hole about female jai alai players, and these three sisters—Becky, Fancy, and Heidi Smith—who were dominant during its heyday that a. could be interesting and b. could be tied to the new jai alai court being built in Miami.

I was very excited to get this email because, as I mention in the story, I grew up in South Florida, which is basically the only place in the U.S. where jai alai is still played. I grew up (underage) drinking in the fronton where Becky used to work. When I mentioned the story to my dad, it turned out that he plays golf regularly with Joey Cornblit, who, if you read the story, you know is generally considered to be the best American jai alai player of all time (that was the easiest sourcing I’ve ever done, and it was a total accident).

The story started out as being about the three Smith sisters.

I tracked down Becky first, who I knew had been the most serious about the sport. Matt helped with this, too. “Becky Smith” is a common name, and he had narrowed it down to a few options. I took his leads and then took a guess using some context clues and comparing old photos to the new ones and ended up being right. I quickly found out that all the other women I had hoped to center the story around — Becky’s sisters, Heide and Fancy, and their mother, Maria Julia — had passed away.

At that point, it became about creating a full story that wasn’t told from the perspective of a single source. I needed more than just Becky to tell the story, which is where the other subjects come into play: Dennis Getsee, who encouraged Becky to start playing again last year and who, I found out a few weeks into the reporting, had been at the fronton the day Heide and her daughter died and was there when Heide’s husband received the news; Jackie Hernandez, who had partnered with Becky in a tournament and played in the school with the three sisters; Joey Cornblit, who could fill out the picture of jai alai’s culture more fully. That’s also where the archival research comes in. Original reporting is the ideal, of course, but old press coverage can fill in gaps, too. It’s how I was able to give Maria Julia a voice in the story even though I couldn’t speak to her. It’s also how I was able to get some details about the sex discrimination complaint that Becky and Maria Julia had filed, since Miami-Dade County doesn’t keep documents past five years.

Sometimes you just get lucky

I thought I was writing a history story, but it ended up being incredibly timely. Again, that was entirely by chance. Once I knew what I had, my goal was to tell Becky’s story, but also to make sure that her mother and sisters got credit for the role they played in jai alai’s history, too. It felt incredibly important to make sure they were all represented to the best of my ability. With so few women having played the sport in any capacity, I wanted each one of them to be recognized.

This is also where I shoutout the Longreads podcasting team, particularly Jason Oberholtzer and Mike Rugnetta. After I sent all my audio their way, we talked about what the podcast might look like and I mentioned one thing that was super important to me. We knew we needed to have someone describe the sport of jai alai, because most people are not familiar with it. I had asked both Becky and Joey Cornblit to describe the sport to me during our interviews. Objectively, Joey’s description was better in that it was more succinct, likely because he’s been giving interviews about the sport for years and has honed his quick explanation of the game. But I wanted to use Becky’s description instead. We were telling a story about Becky breaking a barrier, becoming a pro in a sport that everyone refers to as “a man’s game.”

We needed to use Becky’s telling of how to play the game because it was important to me to establish Becky as the jai alai expert for the listener.

And so that’s what we did (so much thought goes into every little piece of every story, even if you don’t realize it!).

The most nerve-wracking part of this process for me is after a story drops, because 9 times out of 10, my sources/subjects are not happy with the final result. There is always something to quibble with, and it’s really hard for me to know that a subject I worked so hard to portray accurately is upset about the story. But Becky texted me to tell me I’d made her cry, and Dennis Getsee, who was by far my most skittish source and had originally not even wanted to be quoted in the story, texted me after it ran. He had graded the story; he gave it a 10. He’s ready for the movie.