the craft of writing narrative sports non-fiction

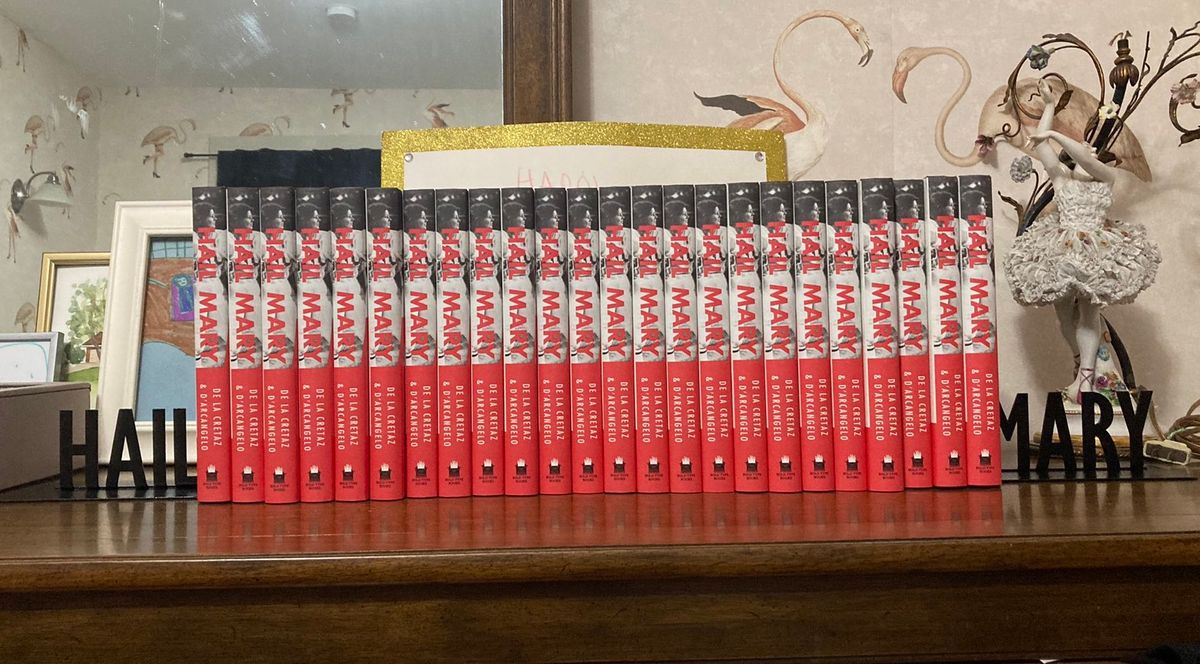

Want to know something wild? I haven't sent an issue of this newsletter since HAIL MARY was released into the world! We had excerpts published many places, including Sports Illustrated, D Magazine, LitHub, Bitch Media, Defector, and Just Women's Sports. We were on NPR and WNYC. I wrote a piece for Jezebel about how reporting the book inspired me to leave my husband, and about the fact that the winningest team in pro football history has been overlooked for The Washington Post. We were featured as an awesome "dad" book (reminder that "dad" is gender-neutral, so get HAIL MARY for your favorite Daddy, Zaddy, or dad). And we've gotten a little bit of praise for the book, too:

“Hail Mary is a glorious and galvanizing chronicle celebrating no-longer-forgotten gridiron greats.”—Oprah Daily

“You’ve likely heard of “A League of Their Own,” a movie that captured the magic of a women’s pro baseball team that once thrived in the U.S. Britni de la Cretaz and Lyndsey D’Arcangelo deliver equally enjoyable stories of another remarkable professional women’s league that got little attention. They showcase the scrappy women’s pro football league that operated in the United States in the 1970s.”—Los Angeles Times, “10 sports books we loved in 2021”

De la Cretaz and D’Arcangelo present an entertaining history of the National Women’s Football League… Without overstating the case, de la Cretaz and D’Arcangelo demonstrate how this overlooked chapter in American sports blazed a successful trail for today’s women athletes. This underdog story is a delight.”—Publishers Weekly

We also have a Super Bowl Sunday event with the National Women's History Museum, which you can register for here.

One thing that I thought a lot about while we were writing this book, and which I have continued to think a lot about since the book published, is the craft process of writing sports narrative non-fiction. Obviously, as the writers of the book, each decision we made within the narrative was an intentional one. Obviously, the structure and tone and voice was deeply considered.

And yet. Sports books are pretty largely ignored by traditional literary and books media. Unless you're writing about, say, Tom Brady, it's hard to convince people that there's an audience for what you're doing. The work is considered to be not literary, or frivolous, despite the fact that sports stories are never just sports stories. Sports stories do not exist in a vacuum. They exist in our society, in our culture, and they are shaped by and tell us so much about the world in whichwe live.

Of course there is craft in writing a narrative non-fiction sports book, just like there is craft in any narrative non-fiction book. A sports book without craft considerations, without a larger story arc, is just a 300-page box score. But I've found it hard to find anyone who wants to talk about that (aside from brief mentions in a Fansided interview and one for the Sports Stories newsletter). So I'm going to talk about it here. I'm writing this in the first person so as not to speak for Lyndsey, but it should be understood that everything I discuss here was a collaborative conversation between the two of us as co-authors.

When writing HAIL MARY, I looked to other narrative non-fiction books for inspiration.

No matter what you're writing, chances are someone has already done it and done it better than you will. Sure, the details will be different, but most of us are not reinventing the genre that our work is going to exist within. So when thinking about the narrative structure of the book itself, I read a bunch of narrative non-fiction as inspiration. Reading what is already out there is great for getting ideas and seeing what other people have done well, but also serves to help you see what gaps your work might be filling or identify things you want to avoid in your own work.

Some of the books that I found the most useful (and I highly recommend all of these):

*Eric Nusbaum's Stealing Home: Los Angeles, The Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between. Nusbaum's book served to give me ideas about balancing many voices and stories, as well as highlighting the specificity around regionality that I knew would feature prominently in our book about a league that existed largely in the Rust Belt (see also: Sam Anderson's excellent book Boom Town). (Eric and I chatted for his Sports Stories newsletter, you can read that here.)

*Bradford Pearson's The Eagles of Heart Mountain: A True Story of Football, Incarceration, and Resistance in World War II America. Pearson's book also deals with a marginalized community coming together and finding purpose and resistance through the game of football, though with obviously higher stakes as his athletes were playing in a Japanese internment camp. But I appreciated the way Pearson balanced his research with the voices of the players and asked larger questions about football, sport, and the world. (Bradford and I did an Instagram Live event together, which you can watch here.)

*Jeff Pearlman's Football For A Buck: The Crazy Rise and the Crazier Demise of the USFL. Pearlman's work is very different than my own, but his book was no less instructive. The book he tried to sell for nearly a decade landed on the NYT Bestseller list and we were able to use that as a comp title in our book proposal to show that there was an audience for a book about a football league. And speaking of, this book was instructive when it came to seeing how another author packaged the story of an entire league into a narrative structure that readers could follow without getting lost, condensing many years and a ton of info into a cohesive story.

*Saidiya Hartman's Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals. While this is obviously not a sports book, Hartman's stunning work was incredibly instructive on a variety of levels. It views marginalized people in history through a modern lens, using historical documents—many of which were incomplete, inaccurate, or filtered through the oppressive lens of the people with institutional power—to tell a more complete story of people that history forgot or framed in a way that didn't acknowledge the truth or complexity of their realities. The book was an example of writing history but changing the lens through which it is told, recentering the narrative on a group of people who have historically been decentered, and working with gaps in the primary source documents.

Deciding where to start: how do you want the reader to receive your characters?

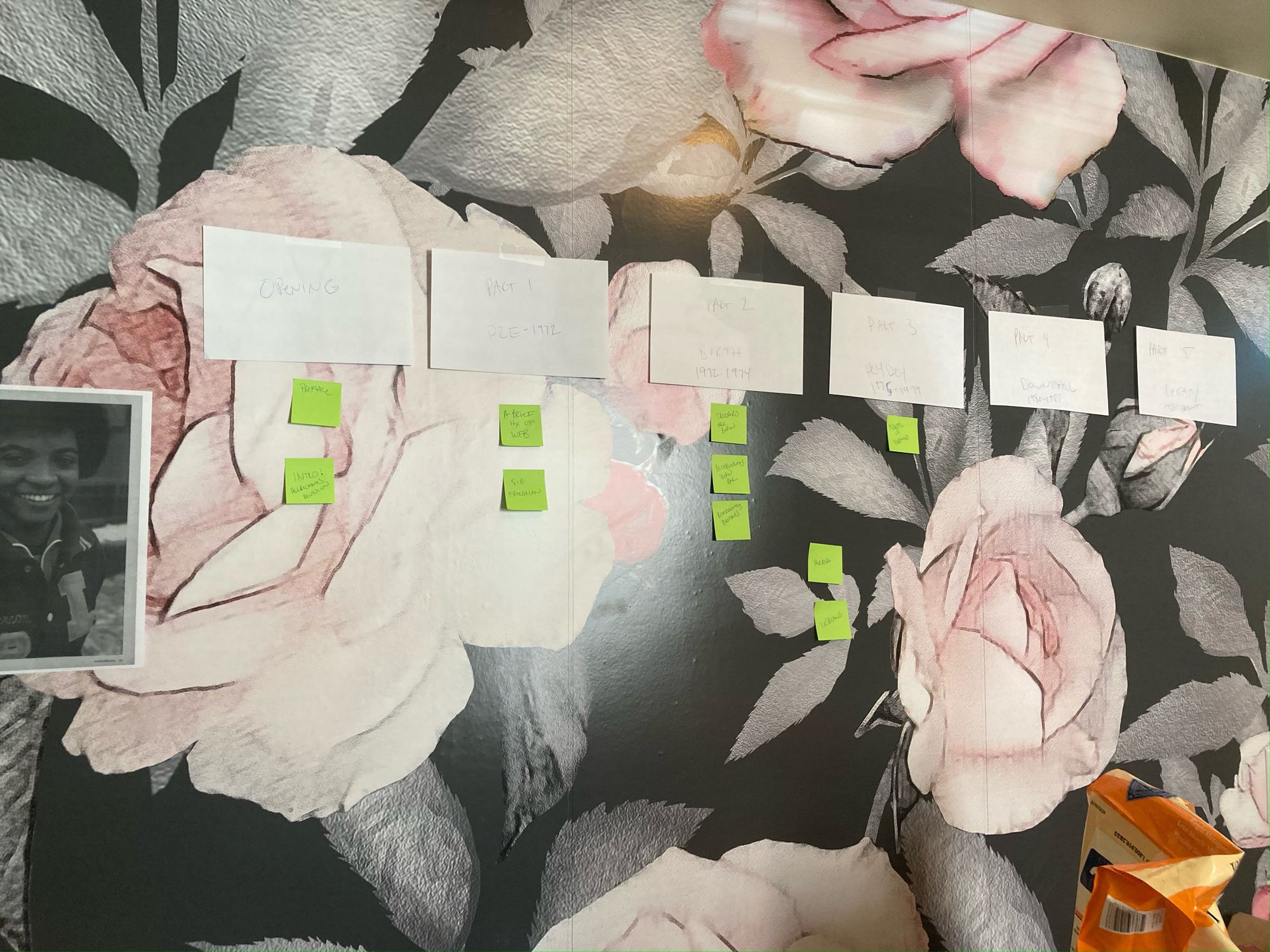

When we wrote the first draft of our book, we began writing chronologically. That made sense, because you can't really know what the structure will look like until you know what material you have to work with. The final book largely kept that structure—except for Part 1. The first part of the book (after the introduction) drops the reader into 1976, smack dab in the middle of the NWFL. That section had previously been in the center of the book and the decision to move it to the front—with thanks to our editor Ben Platt for the idea—was twofold.

1) Part 1 introduces readers to the Oklahoma City Dolls, a new team in 1976. In Chapter 1, you watch them start their season and win their first two games, and then in Chapter 2, you watch them beat the previously undefeated Toledo Troopers, who had five undefeated seasons entering 1976. The reader meets the Dolls as the rest of the league does, providing a nice entry point for the introductory material. But this event—the Dolls handing the Troopers their first-ever loss—is an important one in the larger narrative of the NWFL: it's the moment when the balance of power in the league begins to shift. By dropping the reader into a pivotal moment, there is buy-in to find out what came before—and what will come after.

2) It was incredibly important to us to introduce the players as athletes first and foremost. Women already face stereotypes that they can't play football, that they don't play football, and if they do, they probably aren't very good at it. We never wanted there to be a doubt in the reader's mind that these women were football players. We never wanted the reader to doubt the skill of these women. So to drop the reader directly into gameplay and to have them meet the women on the field, in a game situation, positions them from page one as real, legitimate football players. That way we never have to justify them as athletes or convince anyone of their skill because the reader has already seen it.

Working with the material: using games as natural sources of conflict

One thing that every story needs is conflict. There needs to be tension. Luckily for us, sports provide very natural sources of narrative conflict via games and rivalries. When we first started mapping out the book's structure, one thing we did was look at the NWFL's divisions and which teams played each other. That gave us a jumping-off point for knowing which clashes were going to serve as tension within the narrative, but also allow us to do something else: change the point of view and introduce more characters.

For example: If you look at Chapter 1, you meet the Oklahoma City Dolls first and their upcoming game against the Toledo Troopers is introduced. The natural next step in the narrative is to introduce the Troopers, which we do in Chapter 2. Similarly, after flashing back to give a history of women's football and bring the reader up to the present of the book (the period of the NWFL's existence), you go back to check on the Troopers and are informed about an upcoming game that could change the stakes for the league, playing in Texas Stadium, home of the Dallas Cowboys. So obviously, the next team you meet is going to be the Dallas Bluebonnets, during that game against the Troopers.

Rivalries are another way to create narrative tension and conflict, but they also provide a continuous narrative thread to revisit throughout the book. The brawl between the Detroit Demons and the Troopers? Incredible conflict. The Houston Herricanes' seasons-long quest to defeat the Dolls and whether or not they would be successful in their attempts? A conflict that is threaded throughout the book, that we keep coming back to.

Gaps in the narrative: How do you write around holes in primary source documents and faulty, half-century-old memories?

This, of course, is not a problem that is unique to sports writing. Investigative work will always be juggling this. We also knew that, despite our best efforts, there were going to be errors in our book no matter what we did. But if you're writing about, say, the NFL, you can at least guarantee that the stats you're working with a) exist, and b) are accurate. We didn't even have that.

So, what do you do? You make the inconsistencies and questions part of the narrative! It's what allows us to ask larger questions about why those gaps exist. As we write in the book:

"It's important to remember that the league was viewed through the lens of the people writing about it, not those who were living it... Knowing this context brings up larger questions about the history we think we know. If Hines were not around to correct the record, as researchers and archivists, we would assume that the information reported in the papers was accurate. But aside from the box scores and game recaps, which the reporters generally did well and got correct since they were sports reporters with the skills to write a good gamer, it's hard to know which other parts of the stories are true. The people writing them were largely not equipped to cover sports through a political or feminist lens, or to understand the ways in which their biases colored their work.

History is generally told by the people in power or through the lens of the status quo; the stories written about the NWFL are no different. We don't always know what the players really thought about their experience because the quotes are so shaped by leading or loaded questions being asked by the reporters—if the quotes are true at all."

When faced with almost no documentation about the final years of the league, we leaned into that, too. "Women were still taking the field, but the newspapers had stopped caring enough to write about it," we write in HAIL MARY. "If there's no one there to tell the story, did it ever happen at all?"

The gaps are as revealing as the information you do have. The gaps tell you what people cared to remember or deemed important. They tell you what fell through the cracks. And they provide an opportunity to offer analysis and even, sometimes, speculation. Because while the details are important—and as a history nerd, I live for an obscure find in the archives—the larger story matters, too, and you don't need to be able to recreate what happened beat-for-beat to write a mostly accurate but always compelling narrative about an event.

If you have read and enjoyed HAIL MARY, please consider leaving us a review on Amazon or Goodreads!