turns out I don't suck at writing about sex

I just had to find out what good sex felt like first

When I had originally imagined this newsletter, I intended it to be for writing the “story behind the story” to both promote my work and talk more about the craft and reporting process of storytelling because I’m a nerd for those kinds of things. This edition will be a return to that form.

Today I published an essay at Catapult that has been formally a year in the making, but percolating in my brain since before I even left my marriage. It’s about the near-decade I spent trying to have sex with my husband, my decision to leave, and the liberatory experience of queer T4T sex. (I love you, Mom, please don’t read the essay thank you!!)

I don’t write a lot of memoir/creative non-fiction anymore (something I’ve addressed in a previous newsletter). What that means is that I can take my time with the pieces I do want to write. Like this one, which began with a tweet.

Sari Botton, then the essays editor at Longreads, where I was still a columnist at that time, DMed me to see if I thought there might be an essay here. There was, I said, one that I’d been thinking of along the lines of “everything I tried to fix my sex life before realizing I was just gay,” but that I was too close to the material to write it yet. She said she’d be ready to read it whenever I wrote it.

Then Buzzfeed opened up for pitches for Sex Week and on a whim, I pitched it, thinking it wouldn’t be accepted. It was. I had to write it. Here is what the original pitch for this essay looked like, so you can see how much it changed over time and revision:

HED: I thought I was asexual; turns out I was just gay

PITCH: This is not a coming out essay. I did that when I was 21, to little fanfare. First as bi, then as queer, but always with cis men as an option. A few years later, I met the man I would later marry (in a rainbow dress, no less) — and spent the next decade wondering where the hell my sex drive went. At first I thought it was my new sobriety. Then I thought it was the trauma I was no longer repressing with substances. Then I got pregnant and was sick all the time, so it was definitely that. Then came the nursing, which effectively killed my libido. Then, couples counseling and another pregnancy, which explained that year of drought, followed by nursing again.

At this point, I was starting to seriously consider that I might be asexual. It seemed the only way to explain my lack of desire. I wanted to want sex. In fact, I thought about sex literally all the time — queer sex. That didn't seem weird, because I knew I was queer. Considering that I was in a monogamous marriage, it seemed only natural to fantasize about other people. Plus, I thought, everyone probably obsessively thinks about the theoretical gay sex they are not having (spoiler: only gay people obsessively think about the theoretical gay sex they are not having).

I finally left my husband. It turns out I am not asexual, just really, really gay. But it was only once all the probable explanations for my lack of sex drive were eliminated that I could come to that conclusion, despite all the evidence had been there all along: that rainbow wedding dress; reading the ruling that made same-sex legal in Massachusetts during my wedding ceremony; the book about lesbian Orthodox Jews my husband bought me for Hanukkah the year before we split. What I knew about myself to be true all those years ago had been right all along; trusting my gut (and my cunt) led me back there.

The thought of writing the essay had me feeling quite unmoored so I reached for the structure and security of writing workshops to help me begin. I started in May with a workshop at GrubStreet with Alysia Abbott, one of my favorite instructors. It was called “Touchy Feely: How to Get Emotional Without Making a Mess.” It was there that the first scenes were put down on paper—many of which ended up cut when the essay changed shape later—and gave me something to work off of.

I knew that in order for there to be a revelation and contrast to the “before,” there would have to be an “after.” What that meant was that I was going to have to write about having sex with my partner so the reader could experience the narrator’s transformation. I was nervous about this for a few reasons. One was that I always thought I was really bad at writing sex scenes. The other was that I was writing about sex with a trans partner, while still identifying as cis. I was hyperaware of the history of trans bodies being objectified and fetishized, while also recognizing the need for stories that show trans people as desirable. I wanted to make sure I stayed firmly on the latter side of that line (both of these things would turn out to be miscalculations; I was bad at writing sex because I’d never had good sex and therefore lacked the necessary experience to put feelings/sensations/desires on the page well and my gaze on my partner was not the cis gaze because—surprise! (to no one but me)—I’m trans).

I decided to take another craft workshop called “What Sex Cand Do,” this time with Garth Greenwell, who writes queer sex and desire so beautifully. After that, I crowdsourced everyone’s favorite sex scenes where at least one of the partners was trans. I read them all. In fact, I read so many that I taught a workshop for queer writers this summer at GrubStreet called “Writing the Queer Body.”

Then I wrote and, before turning it in, I hired a transmasculine sensitivity reader to make sure that the section where I have sex with my partner—which felt good to him—read well on a larger platform. The thing about writing about complex identity stuff is that what feels good on a personal level doesn’t always translate to a systems-level and, as a presumed-cis writer, I didn’t want to perpetuate harm.

The sensitivity reader thought the passage read beautifully as being written about my partner and for my partner but worried that on a larger scale, it read like a cis person exploring and discovering their sexuality through the body of a trans person. That, of course, was not what I wanted. I re-wrote that entire section.

I filed to Buzzfeed and awaited edits. Eventually, thanks to pandemic cuts, the essay was killed. I emailed Sari and she accepted the essay at Longreads. Shortly thereafter, she left the publication and moved to Catapult. Luckily she was able to take the essay with her. I filed the piece (again) and waited for edits. Then the piece went on the back burner while I finished writing my book.

This is where things got interesting for me, because during this time—between receiving my first round of edits from Sari and addressing them in a revised draft—I realized I was non-binary. This didn’t change a lot about the essay, but also it changed a lot about the essay. I also realized that I wanted the focus to be less about the list of things I’d tried to fix my sex life and more about the process of revealing myself. The essay covered too much ground; it needed to focus as much as possible. The sex scene with my partner hit different if the narrator’s gaze was no longer the cis gaze on a trans body, but the trans gaze on a trans body. I told Sari there would need to be major rewrites; she was happy to wait.

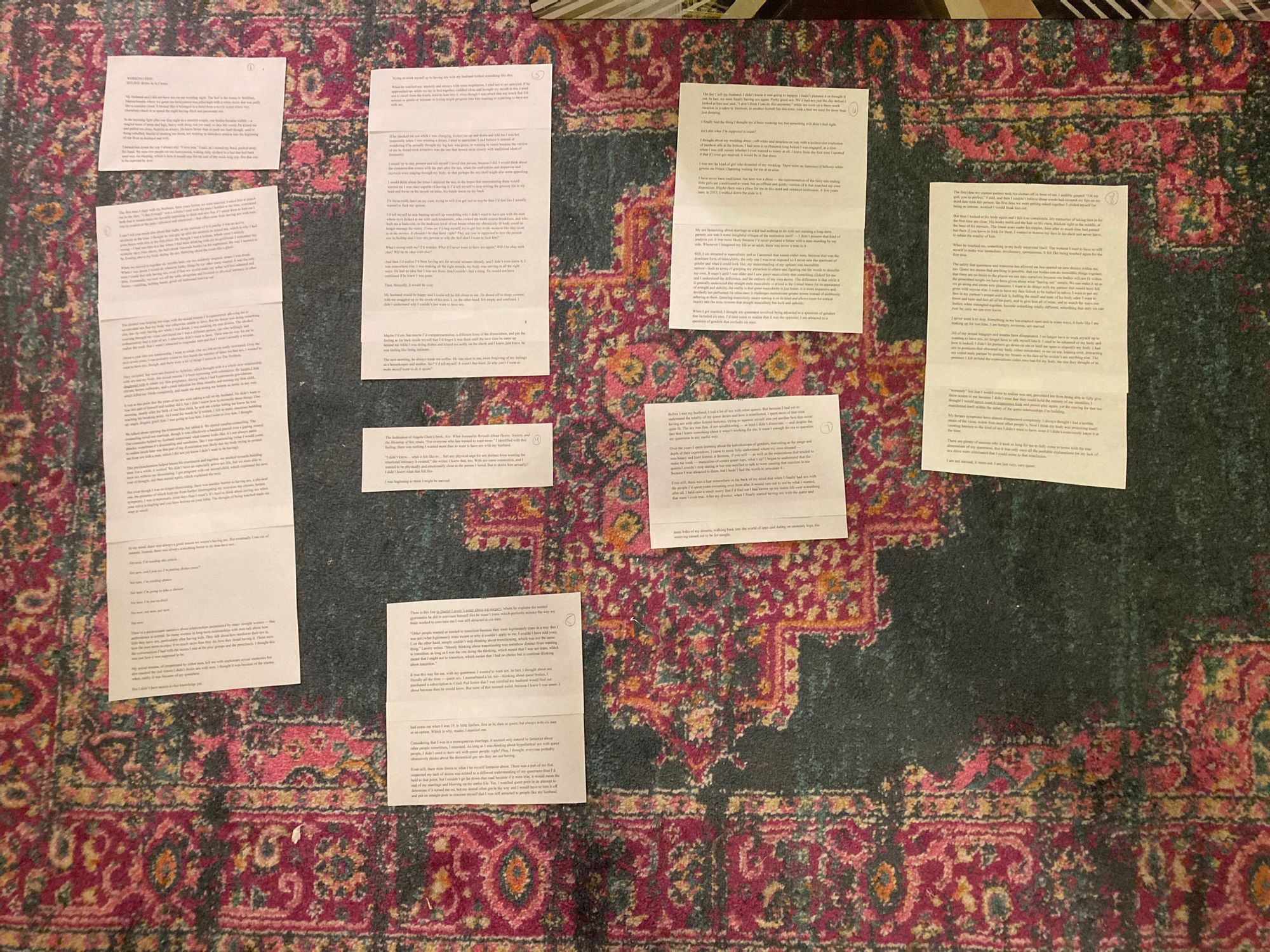

In this phase of the writing process, I had many readers and many eyes on this piece of writing. Two friends did close reads and my writing group workshopped the piece. A very smart friend noticed a mid-graf tense change in the last section and recommended writing the entire section in present-tense to bring the reader closer and differentiate from the dissociation in the rest of the piece. I cut the essay up (literally) and put it back together again. I fought to ensure it did not cater to the cishet gaze in any way, even when it meant back-and-forths with Sari to determine the best way to move forward.

The end result, the first time I’m publicly addressing my transness in a piece of writing and perhaps one of the most vulnerable things I’ve ever written, feels like a raw nerve of mine is living out in the world somewhere. And it happened to publish during Trans Awareness Week, bringing some of the trans joy I’m craving more of into the world.

I also got paid three times for this essay, which ended up netting me more than the $750 my original pitch was commissioned for from Buzzfeed. I got a $150 kill fee from Buzzfeed; $500 from Longreads (my full fee) because I placed it with an editor who then left and they offered to pay me and let me take it elsewhere; $200 from Catapult.

I think that, as writers, we often obscure so much of the work and the craft that goes into creating a piece of work. I want to make that work visible, to let you know it is ok to struggle on a piece and not know where it is going or how it will get there. The process is the point, and will eventually lead you to where you’re meant to be. You just have to give it time to work itself out.

Oh, and if any of the things I’ve written about in the essay resonate for you, you might want to

In Other Writing News…

ICYMI, I reviewed Megan Rapinoe’s memoir, One Life, for NPR:

“One Life is unlikely to convert new fans. In trying so hard to center the book around consciousness raising, Rapinoe loses much of the personal storytelling that so naturally lends itself to doing just that. She is clear with the reader that the reason so many people are willing to listen to her is because she is small and cute and white — recognizing the privilege she has that makes her a less threatening messenger to some white Americans. Her clear-eyed commitment to justice is admirable. But there are others we need to hear from right now, in this moment, where Black organizers across the country helped stop a second-term for Donald Trump.”