my body fell apart & probably won't go back together

but at least i'm still hot & can write a killer story from bed

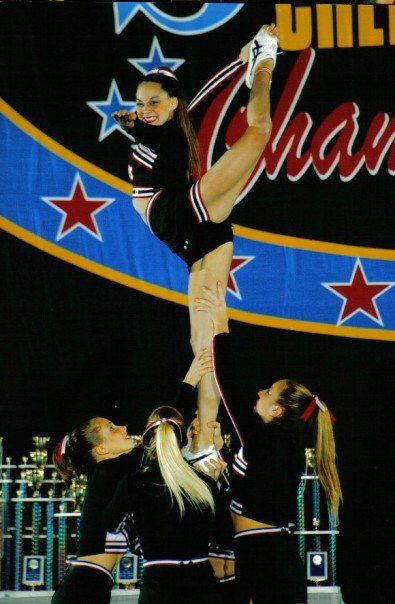

There was a time when my body would do anything I asked it to. I mean, I couldn’t catch a ball or run two miles or accurately shoot a basketball, but I was agile and strong. For much of my life, I was an athlete. Ballet, gymnastics, and competitive cheerleading gave me body awareness, balance, coordination, and immense muscle control. I could stand on my hands and stand on my head and do cartwheels across the beach. I could contort myself into any shape I wanted, my leg effortlessly resting by my head, the idea that not everyone could do splits a source of confusion to me.

It was the latter, my flexibility, that made me a great dancer and gymnast and flyer on top of the cheerleading pyramid. It was also a sign that something was not quite right with my body, though I wouldn’t know it for many years. What I now know is called hypermobility in my joints is the thing that gave me enviable skills, perfect form, and jaw-dropping precision in the tricks I performed. It is also the reason my body is quite literally coming apart at the seams 15 years later. It’s hard to know if the thing I prided myself on and dedicated most of my childhood to actually made my joints worse. It probably did.

The first time I truly remember my body turning on me was when I was in rehab. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been tired. So tired. And not, like, in need of a nap tired. Tired like my mother pulling all the blankets off me in the morning and dragging me out of bed by my ankle to wake me up for school to no avail. Tired like sometimes I fell asleep at my desk at work in the middle of the day. Tired like needing 20 hours of sleep just to function. I started self-medicating with Adderall and cocaine, stimulants to help keep me feeling normal and awake.

But in rehab I started getting unexplained rashes, nerve pain, and muscle aches in my thighs like I’d benched 1,000 pounds despite doing nothing but going up the stairs that day. No one could figure out what was going on, and I was diagnosed with herpes. I was told I had arthritis in my hips, despite being just 26 years old.

The thing that truly broke my body in a way it will never recover from is pregnancy. I was never sure I wanted kids in the first place, and if I knew then that I had hEDS, I probably never would have put myself through pregnancy—let alone have done it twice. But I didn’t know and having two pregnancies 18 months apart tore my body apart from the inside; my joints literally came apart. They’ve never really gone back together. It’s common, it turns out, for pregnancy to accelerate the symptoms of hEDS. It certainly did for me.

But it would take four years until I finally had a name for what was wrong: Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, hypermobile subtype (hEDS). It’s a connective tissue disorder and it affects every system of my body. And, in my case, it means my lower back and pelvis are very precariously held together and sometimes they dislocate. It means my hip joints often ache, from deep inside my body, a constant, chronic thrum. It means I have an ever-present knot on my right gluteus medius muscle, where it’s working overtime to keep my hip in its socket. It means I have no “sitting tolerance,” so I can’t sit in a chair for longer than 15 or 20 minutes without pain, and I spend most of my life lying down in a reclining position—I go from my bed to the couch to the daybed in my office, which I purchased as a replacement for the desk I can no longer sit at. It means I wear a brace on my back and, during the 10 minutes when I had it off the other day, I threw out my back throwing a piece of paper in a trash can. It means I have POTS and can’t stand up too quickly or take baths or showers that are too hot or stand for too long because I might pass out.

I’m starting to internalize terms like “chronically ill” and “disabled” for myself. I’ve seen specialists and what they tell me is that the most I can really do is manage symptoms and attempt harm reduction. There’s no treatment for hEDS. And that’s ok, I’ve accepted that this is how it’s going to be and I am hopeful that through physical therapy, massage therapy, and occupational therapy (all things that have been postponed because of pandemic), I will figure out adaptations that work for me. Each day that goes by I get a better understanding of what my body can and can’t do anymore.

I have a lot of feelings to process around my diagnosis, too. Aside from my internalized ableism that I’m constantly unlearning, I’m really angry. I spent nearly a decade in a relationship with someone who fed me the narrative that I was lazy, that I wasn’t trying hard enough. I internalized that reality. When I received my diagnosis, I sobbed with relief—but also with rage that I had been gaslit to believe that all my physcial ailments were my fault, that I should have been able to control them by just trying harder. I’m also sad, of course, and my body giving out on me in the way that it has feels a bit like a betrayal. I don’t recognize this body anymore; it can’t do so many of the things I expect it to do.

Getting a diagnosis and having a disability flare-up for the first time (likely the result of driving 18 hours back from Wisconsin in two days in July, from which my body has not recovered and was before I had a name for what was going on with me) while in quarantine has been a blessing in some ways. I have not had to go anywhere or do anything. I can rest my body and figure out what it needs. I don’t have to make excuses about why I can’t show up somewhere (again), because I’m not expected to be anywhere. We are all stuck in our homes.

But I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t worried about what is going to happen when this is all over. Are the friendships I’ve forged over Zoom going to be able to survive when I can’t even meet someone for a cup of coffee because sitting is too hard and standing for too long makes me dizzy? Are people going to stop inviting me places when I keep having to decline for accessibility reasons? Is everyone going to forget about me and go back to living their lives when they can, while I’m stuck at home?

Right now I can hide it well. I can position the camera so my brace isn’t visible. I can text back at a leisurely pace and don’t need to reveal that I fell asleep for four hours in the middle of the day. I can (and did) write an entire book from my bed, I can conduct interviews while reclining, and the reality of how low my functioning is at times is unseen.

I’m not ashamed of my disability and I don’t want to lie about it or feel like I need to hide it. I’ve been taking lots of nudes and thirst traps to remind myself I’m still smoking hot. I’m just worried that the rest of the world will pass me by because I can’t keep up. So, that’s how I’m doing.

Follow me!

I’m on Instagram now! I know it’s not, like, the hot platform anymore but with my book coming out later this year, I decided I should have a public account. My current, primary account is private because it has photos of my kids on it. So now I have a public-facing one just for work stuff. I would appreciate if you followed it!

Author Interview: Torrey Peters

I had the pleasure of interviewing Torrey Peters about her fabulous debut novel, Detransition, Baby, for Refinery29. Please read the entire interview! But I wanted to share this one part that ended up being cut, which felt so tender. During our interview, as we were talking about why Torrey ended the book the way she did, my youngest kid came in asking for a treat.

Britni: Oh, hold on. I have to get my kid a piece of chocolate; she had vaccines today so she’s getting bribed with whatever she wants for being so brave. OK, back, sorry!

Torrey Peters: I mean, you're doing it right there, right? You are the answer to the book, you and your partner, what you're doing now [raising a family together], the books can't anticipate that. But the book points to your situation. There's going to be a matrix of many, many people solving this each in their own way.

After I finished the book I ended up meeting my partner, who has a nine-year-old, and the family situation that we've ended up working out is not one I would have ever anticipated. And it's not one that the book anticipated, but it seems to be working for me.

What I would like the book to gesture towards is the accretion of your situation plus my situation, plus thousands of other situations where we say, ‘let's try, let's each of us try.’ What I want those characters to do is, I just want them to try the same way that you're trying. That's what I was aiming to do with that kind of ending, and whether it's successful or not, I leave that to critics.