In June, during Pride Month, I drove to Cape Cod to attend Camp Gaylore, a weekend-long camp for Gaylors—queer Taylor Swift fans. You can read my account of that weekend over at Cosmo now, but I wanted to share some personal reflections (most of which did not make the final story).

I'm also doing a Q&A over on TikTok about the process of writing this story because there are a lot of questions and speculation from the fandom about how involved Taylor's team was or was not (they were not). But I love doing media literacy and talking about process so go check that out!

I was a Gaylor before I was a Swiftie. Or maybe, I am a Swiftie because I am a Gaylor.

I left my marriage to a straight man in the summer of 2019, right about the time the Lover album was released. I was familiar with whichever of Swift’s songs had been on the radio and I definitely wasn’t a Swift hater, but I wouldn’t have considered myself a fan of her music. That September, I moved in with friends of mine—a lesbian couple—while I tried to find somewhere else to live (one-half of that couple had stayed with me and my ex-husband when they’d divorced their own husband because they were gay; now they were returning the favor).

Lover, with its pastel-hued cover, LGBTQ+ anthem (“You Need To Calm Down”), and catchy pop tracks got a lot of airplay in that two-bedroom apartment. There were plenty of love songs on the album, as implied by the title, but there were breakup songs, too. “Death By A Thousand Cuts” recounts the slow, painful death of a long-term relationship—not unlike a divorce. “I Forgot That You Existed” gave me hope that I could reach a level of indifference one day. Even still, the album felt a bit like fluffy, empty calories to fill my head during a time when I needed relief from all of the heaviness around me. I knew nothing yet of Gaylor theories, of the belief that Lover was supposed to be Swift’s coming out album, of her rumored relationship with supermodel Karlie Kloss that supposedly inspired most of the songs (their ship name is "Kaylor").

Then, the pandemic happened and Swift surprise-dropped folklore, just a few months after my divorce had been finalized over a conference call. I immediately noticed that every lesbian I knew seemed incredibly excited for this album and I realized I must have missed something. Why do all the gay women I know seem to love Taylor Swift so much?

I went looking for my answer and very quickly discovered Gaylor theories. I went back to Swift’s discography, which I had never listened to in full, with an eye towards sapphic themes. I listened to the album Reputation from front to back—an album that was marketed as Swift not caring about what was said about her in the press but that, if you actually listen to the lyrics of the songs, is about a love affair with someone that could destroy Swift’s reputation, a love that must be kept private and secret, a love that Swift is willing to lose everything for. It was hard to imagine any of the white, cishet men Swift had been publicly linked to being controversial enough to ruin everything for her. It was hard to imagine the song “Dress,” with its lyrics about not wanting someone like a best friend, being anything but sapphic.

Regardless of what Swift’s sexual orientation truly is, she writes gay music. Singing of secret, hidden relationships, of friends-to-lovers tropes, of longing and forbidden desire—all of these things are common queer experiences.

Many Gaylors actually credit the community, and the queer readings of Swift’s art, with helping them learn about and feel connected with the queer history they wouldn’t otherwise know. Through references in Swift’s work, members of the Gaylor community have learned about the significance of the color lavender in queer history, about Emily Dickinson’s relationship with Susan Gilbert, about Stonewall and hairpin drops and Sappho and the term “friend of Dorothy” and the rumors about Marie Antoinette. Through analyzing Swift’s art from a queer lens, it teaches them the signs—the hairpins—that queer people have dropped throughout history in order to signal to other queers that they are one of them.

Camp Gaylore was not my first time at the Craigville Retreat Center, a sprawling collection of buildings that look sort of like if the town of Stars Hollow was dropped onto Cape Cod. I have been one other time, with my children and my husband when he was still my husband. We were attending a retreat with our synagogue. Joining a shul was something I had done after Trump was elected, as a way to connect with Jewish community in an increasingly hostile political climate.

If I’m honest, being a member of a synagogue was something else, too: it was what I thought I was supposed to be doing. It was what I thought “normal” families did, what happy families did. I was trying really, really hard to fit into the straight life I had built for myself, despite the gnawing sensation that something wasn’t right. I had gravitated towards the temple we joined because of the large number of two-mom families who attended. I surrounded myself with queer families as a way of feeling like I was in community with other queers even though my home life was so incredibly straight.

I think about this often when I see photos like the ones from Swift’s Grammys party— Swift, surrounded by nearly every major lesbian pop artist, including Hayley Kiyoko, King Princess, and Fletcher. Or when I look at her list of tour openers (MUNA, Girl in Red, Pheobe Bridgers) or the surprise guests she’s brought out over the course of her career (Tegan & Sara on the Red Tour, Kiyoko on the Reputation Tour—who sang her song “Curious,” at Swift’s insistence, days after Karlie Kloss’ engagement to Josh Kushner was announced).

This idea, of hiding in plain sight, of screaming to be heard from within a straight marriage (or a straight public image), is one of the themes that resonates the most for me when I think about queer readings of Swift’s music. The longing and love are beautiful, but they are also sad. They are lonely.

In the music video for her song “Delicate,” Swift imagines a world in which she is invisible to the people around her. On-screen during The Eras Tour, a giant version of Swift waves her arms and tries desperately to get the crowd to see her but the implication is that they can’t. “They see right through me,” Swift sings on her song “The Archer.”

It is a feeling I know well, one I could only get rid of by living an actively, openly queer life surrounded by other queer people. It’s a feeling that Gaylors know, too, and it's why they find so much solace in a community that reads the work of their favorite artist through the same lens that they do.

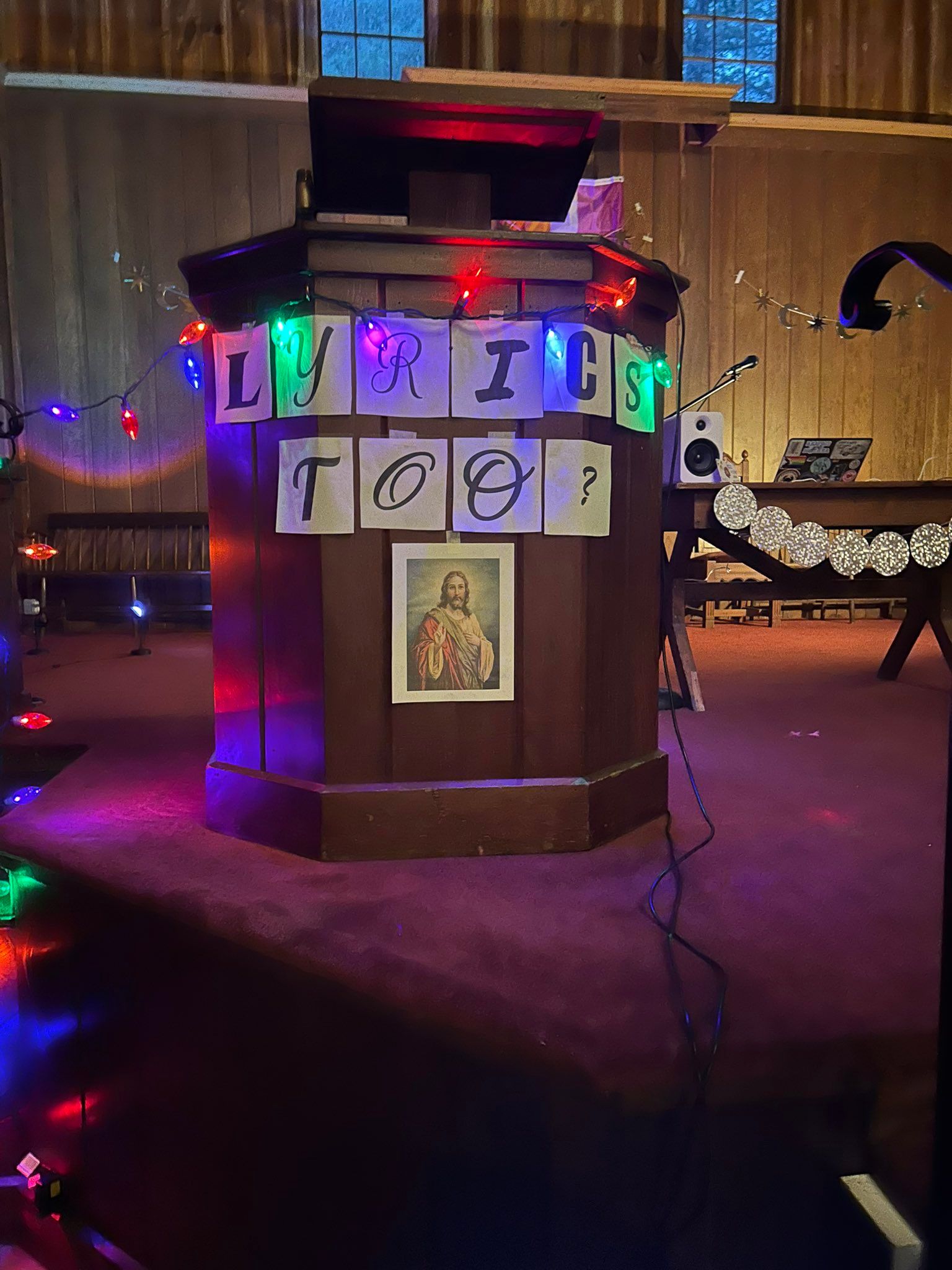

Gaylors are maligned by the larger Swiftie community, sometimes being harassed so badly by straight fans (known as Hetlors) that they have to delete their social media accounts. Even in a gathering of 70,000 Swifties like the Eras Tour, which many of the campers have attended, their acceptance is conditional, not guaranteed. Here at Camp Gaylore, it is unquestioned, full-throated. As the song "Cruel Summer"—a song off the Lover album, and which has gone viral enough on TikTok this summer to be released as a single four years after the album initially came out—reaches its iconic bridge during a queer prom in a white chapel, 40 voices scream-sing the words.

Yes, they say to each other. I see you. Or, as Swift sings on the lead single, lesbian anthem, and vault track by the same name on the newly released album Speak Now (Taylor’s Version), “I can see you.”